Services - Equine

Equine

Please click on the links below to help you:

Setting out to buy a horse, especially for the first time, can seem a very exciting prospect, however, it can also become a very frustrating business indeed. You have your dream horse in your mind’s eye and the search begins. If you are very lucky, you find what you are looking for and if you are really lucky it might not even take very long, but, far more likely, you will travel the length and breadth of the countryside looking at horses that don’t remotely resemble the equine paragon in the advert you answered. Then finally – bingo! – you find a suitable horse, and decide to take the plunge. The seller looks you straight in the eye and says that the horse has never had a day’s illness or lameness in its life and may even offer to take the horse back if you are not happy with it. So far, so good, but…!

Barely a month goes by without us hearing the above history from a worried new owner who is now having problems. Unfortunately some of them are about to have a very painful, and possibly expensive lesson in the many pitfalls of buying a horse. Whether you are buying a horse for £500 or £25,000, doing so without some form of pre-purchase examination is a very risky business. At the time, it may seem that you are saving money but it can cost you dearly in the long run. Always remember that, no matter how experienced you are, it is worth taking someone knowledgeable along with you when you go to see and ride the horse – another pair of eyes on the ground is invaluable – and your advisor may well stop you getting carried away and going for something totally unsuitable. You are about to part with your hard earned cash so what are your various options? Would you buy a house without a survey?

Buying any horse is a risk and a vet is able to help you objectively assess some of that risk factor and give an unbiased opinion as to the horse’s physical suitability for the intended purpose. The perfect horse has never been foaled. All horses collect lumps, bumps and battle scars – some quicker that others! The art of vetting is assessing what will realistically affect that suitability, or a possible future sale by you.

Temperament is not included in a vetting – that’s someone else’s pigeon! One word of caution on the subject of temperament – beware of the thin horse with the docile, quiet nature – feeding and increased health can have a dramatic effect and you might suddenly find yourself bouncing around the countryside on a raving lunatic with your adrenalin levels through the roof!

Purchase without examination

It always amazes us how many people undertake the expense of buying a horse with no examination at all. Fair enough if they are very experienced and are satisfied that they can assess a prospective purchase, with the exception of heart, wind and eyes, they are probably right. However, there have been several cases where a horse has been purchased for a considerable sum and because of problems which have arisen, the horse has then undergone a PPE and failed. Where does the purchaser go from there?

Most people who buy without any examination are relatively inexperienced or first time buyers. This is often because they accept that what they are told about the horse is true. One of the things that develops with horse-buying experience is a healthy scepticism! The world is full of people who become somewhat economical with the truth when selling a horse! The problem is often not what they say but what they don’t say about the horse. Learning to ask the right questions is an art form. We can recall many instances where an innocent client has been lulled into buying a temperamentally unsuitable or unsound horse.

Five Stage Prior To Purchase Examination (PPE)

This examination is often described as a “full vetting”, takes about 2 hours and includes the following stages:

- the preliminary examination

- the trot up

- strenuous exercise

- a period of rest

- the second trot up and foot examination

The purpose is to identify those factors of a veterinary nature that might affect the horse’s suitability for its intended use so that the prospective purchaser can make an informed decision as to whether or not to go ahead and buy the horse. This is by far the preferred examination from the veterinary surgeon’s point of view as it allows them to examine the whole horse both at rest and having undertaken ridden exercise. If the horse passes you will be issued with a certificate which identifies the horse, details the veterinary findings and gives an opinion as to the suitability for the intended use. This certificate may be required for insurance purposes.

To get the very best out of this examination various prior arrangements need to be made. If the horse is some distance away ask your own vet if he can recommend someone in the locale – do not use the vendor’s own vet as this could put everyone (especially the vet!) in a difficult position. Contact the vet prior to the examination to let him know what you want to use the horse for, any of your own observations and to give any special instructions (blood tests and x-rays are not included).

Make sure there are suitable facilities to carry out all phases of the examination – a rough, stony, mud bath on the side of a hill will not suffice. This will be a waste of the vet’s time and, more importantly, a waste of your money! Ensure that there is a competent person to assist the vet during the examination and also an experienced rider who must be able to remain in balance trotting and cantering in tight circles, and not be afraid to gallop the horse. The horse should be well shod and have suitable well fitting tack. All of the foregoing will give the horse the best chance of passing the examination – which, after all, is what everyone wants.

Limited Prior To Purchase Examination (LPPE)

There may be a number of reasons why vets may be asked to perform a shorter version of the full PPE:

- cost of the full PPE

- the horse may be well known to the purchaser

- the horse is unbroken

In the LPPE only the first two stages of the PPE are done. Moray Coast Vets always recommends the full PPE, but we would far rather undertake an LPPE rather than no examination at all. It is all about limiting risk for the buyer.

We recommend that horses are vaccinated against tetanus and equine flu.

Two doses are required to protect your horse, with 4-6 weeks between each dose. You can start from twelve weeks of age.

Equine Flu

After the initial primary two vaccinations as above, for FLU protection, they must then have a booster between five and seven months after the second dose and subsequent annual boosters which should be WITHIN one year of the last booster.

This “less than 365 day” rule is paramount if your horse is ever going to any premises where Jockey Club rules apply. This could be going to summer pony-club camp or many large shows and events. Even if the vaccination interval is one day over the 365 day permitted limit, he may well be excluded from such events and the primary vaccination course started again. A horse is never too old to vaccinate.

The vaccines we now use have the most up-to-date flu strains with a high purity and very low level of vaccine reactions.

Tetanus

After the primary vaccination course, the tetanus part only has to be done every TWO years to fully protect your horse.

If everyone saw a case of tetanus then ALL horses would be vaccinated. Horses are extremely sensitive to the Tetanus bug. A dog is 200 times less likely to contract tetanus – and we even VERY occasionally see them affected. It is the small puncture wounds (which you miss), rather than the big bloody wounds, which are most likely to allow entry of the Tetanus bacillus which can lie dormant in the soil for MANY years – so VACCINATE! The bacterium produces a toxin which interferes with nerve function, causing massive fit-like spasms and eventually respiratory distress and death. There is no cure, just prevention by vaccination.

Worming your horse is an ever-changing subject, which can be very confusing.

Signs of worms in your horse can vary from no signs of disease to very dramatic disease such as colic from impactions, gas filled intestines, rupture of intestine, intussusception (where one part of the intestine prolapses into the lumen of the adjacent part of intestine), death of part of the intestine due to damage from the worms, diarrhoea and weight loss. Other less common signs of worms can be ulcers, coughing, poor coat, decreased weight gain, itchy skin and urticaria.

Diagnosis of a worm infestation in your horse can also be difficult. It cannot be based just on the signs listed above as they can be signs of other types of disease and so are not specific to worms. Worm egg counts from a sample of faeces from your horse are very good when we get a positive result but a negative worm egg count could mean the worms in your horse are not mature enough to produce eggs yet, are not a type of worm that produces eggs in large quantities, or eggs of a type not easily seen when the faeces sample is analysed. Tapeworms and cyathostomes are examples of worms that are difficult to diagnose on faecal analysis. There is a blood test (an ELISA) available to look for tapeworm. The blood test gives a result which tells us the level of infection (low, moderate or high) but a high result goes down very slowly after treatment. Work suggests that after treatment, it can take 12 to 16 weeks to go from a high to low result on the blood test. However re-exposure from the pasture in this time will stop the result from going to low.

It is therefore much better to introduce a treatment strategy for internal parasite control in your horse. The most effective thing you can do is reduce your horse’s exposure to worms by minimising over-grazing and regularly removing dung from the pasture. If this is not possible, rotation of the pasture or mixed species grazing horses with cattle or sheep will reduce the worms on your pasture. The next best strategy is to target anthelmintic treatments (wormers) only to the horses with a worm infestation. This requires regular worm egg counts on all horses and tapeworm ELISA blood tests from all horses which can both be provided by Moray Coast Vets.

Often these control measures are impossible to introduce and so we rely on the use of anthelmintics (wormers)alone. This does not mean you should not still pick up the dung and reduce over-grazing of the pasture. Grass harrowing of pasture in dry weather will desiccate (dry out) worm eggs and larvae so killing them, so it is a good aid but should never be done in damp weather as this would spread the worm eggs and larvae around the field.

The common worms that horses in the UK get are:

- Large Strongyles (Strongylus vulgaris, Strongylus edentatus, Strongylus equines);

- Small Strongyles (Cyathostomins – more than 50 known species, Strongyloides westeri);

- Ascarids (Parascaris equorum – most problematic in foals);

- Tapeworms (Anoplocephala perfoliata, Anoplocephala magna, Anoplocephaloides mamillana)

- Lungworm (Dictyocaulus arnfieldi).

Essentially their life cycles are similar. Eggs are passed out in the dung, larvae hatch from the eggs and crawl up grass. This grass is eaten by the horse and the larvae develop inside the horse into adult worms which lay eggs and the cycle continues.

Infectivity of the worms depends on a multiple of factors:

- Weather is very important – the larvae need warm damp conditions to hatch and crawl up the grass;

- Age of horse – young, old and sick horses have less natural resistance to worms;

- Pasture management – horses naturally will not eat near their dung thus in the wild they would not pick up many worm as the worm larvae cannot crawl far. If the pasture is overcrowded, then especially horses lower in the pecking order will eat near dung and can pick up worms.

The larvae can survive on the pasture if environmental conditions are good (warm and moist) but most infection on the pasture is in the form of eggs that are very long lasting. This means that pastures need to be left without horses on for at least a year to be clear of infection.

There are five chemical classes of anthelmintics licensed for use as wormers in horses:

- Moxidectin (e.g. Equest),

- Ivermectin (e.g. Vectin),

- Pyrantal embonate (e.g. Strongid P),

- Fenbendazole (e.g. Panacur)

- Praziquantel

Praziquantel and double dose Pyrantal embonate are the only ones that will kill tapeworms.

Moxidectin and a five-day course of Fenbendazole are the only ones that will kill cyathostomes when they are encysted (especially during the winter, cyathostome larvae burrow into the wall of your horse’s intestine and hibernate in a little cyst over the winter to hatch in spring.)

The other worms should all be killed by moxidectin, ivermectin, pyrantal embonate and fenbendazole.

Lungworm is rarely seen nowadays and is very effectively treated with either moxidectin or ivermectin.

The problem with using drugs is that resistance to them develops over time. Some studies put the level of resistance to fenbendazole at 80-90% and pyrantel embonate at 30-50%. A single report of ivermectin resistance in Lincolnshire has been published, with no reports of moxidectin resistance to date. We need to use drugs in a controlled manner to try and reduce resistance development and so preserve the effectiveness of them. How to use drugs in such a way as to minimise resistance developing is a controversial subject. There have been examples of resistance developing as a direct result of the incorrect use of cattle anthelmintics in horses, so we always advise the use of equine licensed products. Everyone worming a horse should use a weight tape so the dose given is accurate.

Our advice at Moray Coast vets is to isolate and treat all new horses with moxidectin and praziquantel and keep boxed for 48-72 hours. We then recommend a monitoring system throughout the year with worm egg counts to determine if worming is then necessary.

Summary

1) Reduce over-grazing of pasture.

2) Remove dung from pasture, ideally daily but weekly in colder months and two to three times per week in the warmer months if daily is not possible. Grass harrowing is helpful but should never fully replace collection of dung as it requires particular weather conditions to be effective.

3) Rotate pasture with other livestock or arable land on a two to three year rotation. If this isn’t possible mixed grazing with cattle or sheep may reduce pasture burden and resistant populations of worms.

4) Carry out faecal worm-egg counts every three to six months and only treat with anthelmintics if strongyle egg counts are greater than 200-250 eggs per gram. Tapeworm ELISA (blood test) should be performed every twelve months. Treatment should be administered if moderate to high exposure is diagnosed on the ELISA.

5) If the testing above is not possible, then selection of anthelmintic groups should be done in conjunction with us and tailored to your individual situation. Anthelmintics should be administered at appropriate dosing intervals for the drug used (for example every 13 weeks for moxidectin, eight weeks for ivermectin, six to eight weeks for pyrantel embonate or fenbendazole.) Double dose pyrantel embonate or praziquantel should be administered in late autumn or early winter (October or November) for treatment of tapeworm infestation.

6) If horses on the same premises are to be wormed regularly, all animals should be wormed at the same time with the same product. Ideally, animals should be stabled for 48 hours after anthelmintic administration.

7) All new horses should be isolated when arriving at new premises and be treated with anthelmintics that are effective against small strongyles and tapeworm. They should be stabled for 48-72 hours after administration.

Teeth

During the first nine months of life a foal will develop six upper and lower incisor teeth (grazing teeth) and six upper and lower cheek teeth (chewing teeth). These teeth are milk (deciduous) teeth and will be replaced by permanent adult teeth at specific times from approximately 2½ to 4½ years of age, and by five years of age a horse will have a full mouth of permanent teeth. These consist of six upper and lower incisors, four canines (not always but most commonly in geldings) and twelve upper and lower cheek teeth.

Regular annual dental care is necessary because of the structure and pattern of wear of horses teeth. The grazing horse spends at least 12 – 14 hours of his day tearing and grinding grass and his teeth have specifically evolved in construction and shape to maximise efficiency for this. They are coated with extremely hard enamel to cope with the continuous grinding action. The cheek teeth are rectangular in shape and are in direct end to end contact to make a continuous ridge of solid enamel surface. To cope with the inevitable wear, the teeth continue to grow into old age, when the growth declines and the teeth gradually wear down and fall out. The two grinding surfaces are the upper and lower cheek teeth on both sides of the mouth. During the grinding process the force applied is not consistently even over the entire surface i.e. the outer surface of the upper cheek teeth and the inner surface of the lower cheek teeth receive less force than other areas. This reduces the wear on these surfaces and allows the development of sharp enamel points (SEPs). SEPs can easily injure the soft, sensitive cheek areas especially when the bit is in the mouth and causing pressure. These points are normal features of a horse’s mouth but must be removed by filing with specialised rasps for the horse’s comfort and welfare, and for your safety when riding.

On average it takes about a year for these sharp points to redevelop and cause a problem so our annual inspection should be adequate (however, do remember that, like us, all horses are individuals, and some may require more frequent examination!). To make a thorough examination we need to use a mouth gag that will allow both a visual and manual examination of the teeth. For safety, any examination with a gag should take place in a confined area i.e. a loose box. Initial examination of the incisors is made before the mouth is opened and the gag is fitted. Most horses will co-operate willingly with this examination but, very occasionally, and probably due to some previous bad experience, a sedative is required – more so for more advanced problems and examinations. The inside of the cheeks is examined visually for signs of damage and the general shape and condition of the enamel surfaces is noted. A manual examination of the cheek teeth is then made for any abnormalities or spikes and for the presence of wolf teeth. A dental mirror, after a mouth wash, is used to check the buccal (inner) surfaces. Enamel points are removed by rasping and a variety of size and shape of rasp are required to reach all areas of the mouth. A straightforward rasping of spikes where no abnormalities are present will take approximately five minutes. More advanced remodelling, which can take a few visits, is done using an electric power-float with a diamond-impreganted grinding surface.

This can often be avoided by annual veterinary attention. We consider an annual dental examination and treatment if necessary can help prevent major dental problems occurring later on in life. It will also help keep your horse happy and comfortable when ridden and therefore improve safety and control for you. It makes good financial sense to combine the annual dental inspection with your horse’s yearly vaccination. As a vet, dental care is a job from which we get a great deal of satisfaction – we would rather prevent a problem than have to deal with it, any day. Dental care is a vital part of a horse’s health programme.

What sort of common problems can arise with horses’ teeth?

Let’s start by looking at youngsters under five years of age. Yes! – surprisingly enough, young horses do get dental problems. A lot of change and development takes place in the early years starting with the development of milk teeth during the first nine months of life then the replacement by permanent adult teeth between 2½ and 4½ years of age. We commonly see problems associated with the loosening of the milk teeth, particularly the cheek teeth, primarily the dropping of food, particularly hard food, or the reluctance to eat fibre such as hay. Unfortunately, it’s not uncommon for these enamel caps to break and leave pieces of tooth embedded in the sensitive gum. We are not in favour of removing milk teeth unless they are causing a problem but if there are symptoms to suggest a loose or fractured milk tooth, get Moray Coast vets to make a full mouth examination. These teeth are easily removed.

Another commonly problem found in youngsters is swellings on the lower jawbone or mandible. These swellings are usually associated with the development of the adult cheek teeth. The single rule of thumb is that if they are symmetrical i.e. equal size and present on both jawbones, then they are likely to be normal tooth development and will disappear as the horse gets older. However, if the swelling is on one jawbone only, is hot and painful to touch, or is discharging, then you probably have an abscessed or impacted tooth. The permanent cheek teeth erupt so that the last one to grow in is the third cheek tooth, and it has to force its way into a small gap. By doing this it eliminates any gaps between the cheek teeth so that you have a continuous enamel ridge or grinding surface with no gaps where food can be trapped and subsequently cause gum disease. On occasion there is insufficient space for this tooth to erupt so any suspicious lump should be x-rayed to ascertain if this is the problem.

In the middle aged (between 5 -15 years) horse, the most common problem we see is laceration of the cheeks caused by large enamel points. Removing these points is of paramount importance to the horse’s wellbeing as it re-establishes an even surface for him to efficiently grind and chew his food prior to swallowing. We spend a great deal of money feeding a horse so we want to maximise the nutritional value he gets from it. Providing a smooth surface also allows us to use a bit and bridle without causing pain and damage to the horse’s sensitive mouth. Vets should use a mouth gag when rasping a horse’s teeth so the next time your horse is being rasped ask if you can feel these spikes for yourself. Once you have felt these spikes, particularly on the outer surface of the upper cheek teeth, you won’t need any further convincing about the importance of regular rasping! Many a poor horse has been called everything under the sun for being difficult to ride when, in actual fact, he is in extreme discomfort.

A very common problem in as many as 15% of horses is the development of large hooks on the front of the first upper cheek tooth with an associated large hook on the back of the sixth lower cheek tooth. This is caused by the upper arcade of teeth being slightly more forward than the lower arcade, therefore an area on the first upper and sixth lower is not in wear. These hooks can grow so big that they catch the gum on the opposite jaw when the horse chews – ouch!! No wonder these horses tend to lose weight and will often spit out food, particularly hay, having tried to chew it. If you find little balls of rolled up hay in your horse’s box he may have this problem. Regular dental rasping will prevent this developing – in young horses you may have to rasp every six months as it is this period of the horse’s life that the teeth are erupting fastest. In older horses we see a huge range of different problems, many of them associated with abnormal wear during the middle years of life. Problems will be minimised by inspections every year.

As the horse reaches its senior years, the growth slows down, but not always all at the same rate, and we often find a wave appearance developing in the cheek arcade instead of two flat surfaces that can grind against one another. This makes chewing more difficult and less efficient – so the horse will lose weight, particularly in the wintertime, and this needs our more specialised equipment to make repairs. Hay is the most difficult food for the horse to eat, it’s dry, the stems are long and it has to be well ground before it is swallowed. If your horse is not eating the expected quantity of hay then there may be a problem developing. Loss of weight is the most common symptom of teeth problems.

Lameness is the most common reason for us to visit horses. Most causes of lameness are found in the foot! Abscesses of the sole are very common are mostly a complication of a puncture wound, which has become septic. These are pared away to allow drainage and subsequent healing, along with antibiotics.

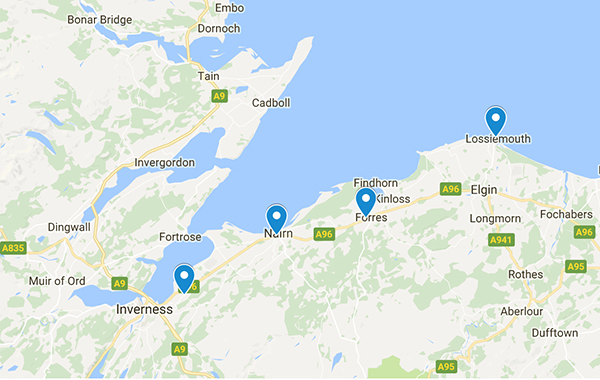

Most lamenesses are diagnosed and cured after the first visit, but it may be necessary to use nerve blocks or take xrays to come to a diagnosis. We may ask you to bring your horse to our Forres surgery for further investigation. Navicular disease is is an example of this. Here, the Navicular bone becomes rarified – it is thought, due to changes in its blood circulation, causing poorly calcified areas in the bone due to deprived blood supply/oxygen and it becomes weak and painful.

This condition often causes stumbling, with the horse sometimes tripping and falling to its knees – usually on hard ground, where the concussion effect is greatest. Once diagnosed, long treatment can produce good recovery from this chronic condition, but some horses are limited in what work they can do. The earlier a condition is seen, the better the chance of resolution.

Diagnosis of acute lameness may involve ultrasound scanning to assess the severity of, for example, a tendon sprain or tear. Ultrasound scanning can also be used in the early diagnosis of pregnancy.

Laminitis (or founder) is caused by inflammation of the sensitive tissue or lamina, within the hoof. This swells but cannot expand due to the hoof surrounding it and so causes pain and unwillingness to walk. The horse has an appearance of leaning back when standing – the horse’s way of taking pressure off the toe. It may affect all 4 feet but one may be worse than the others. If it progresses, the pressure causes the last bone in the leg (pedal bone) to rotate so that the tip presses on the sole causing even more pain and eventual penetration of the sole in the most extreme cases. These extreme cases result in euthanasia. Obviously it is better to prevent this in the first instance.

(the following text is from the laminitis trust where more information is available)

You can prevent laminitis by avoiding high risk situations. The following is a list of causes or circumstances which we know commonly precedes the onset of laminitis.

- 1. Obesity from general over-eating (=over-feeding!)

- 2. Overeating on foods rich in carbohydrate or rapidly fermentable fibre i.e. cereals, coarse mixes, rapidly growing or fertilised grass – especially in the Spring and Autumn but in a wet year there is potential for laminitis during all the growing season. This is the most common cause.

- 3. Any illness which involves a toxaemia. This may be a bacterial infection or following the ingestion of plant or chemical toxins.

- 4. Cushing’s Disease. This is a condition which follows an abnormality affecting the pituitary gland in the horse’s head. It results in the horse failing to shed its winter coat. The coat becomes long and matted and eventually curly. The horse drinks and eats increased amounts of food while sweating excessively and losing weight. All Cushing’s cases suffer laminitis.

- 5. Weight-bearing laminitis. When the horse is severely lame on one leg and has to put all his weight on the opposite limb they often suffer from founder in the weightbearing limb. This is particularly common in hind feet.

- 6. Concussive laminitis (road founder). When horses are subjected to fast or prolonged work on hard surfaces they may develop laminitis as a result of trauma to the laminae, particularly if their horn quality is poor.

- 7. Hormonal problems. Animals which are “good doers” may be hypothyroid or have an abnormal peripheral cortisol enzyme system. The latter condition, recently described has been called obesity related laminitis or peripheral Cushing’s disease. Others develop laminitis when they are in season.

- 8. Cold weather. A few horses show laminitis during cold weather. Fitting warm leg wraps during cold snaps prevents the problem in most cases.

- 9. Stress. worming, vaccination, traveling or separation from a “friend” can trigger an attack of laminitis in a few horses.

- 10. Drug induced laminitis. Although some wormers can precipitate laminitis, the most common group of drugs which cause laminitis are the corticosteroids. Even injecting short acting corticosteroids into joints can cause severe laminitis. This is why we never routinely use these in drugs at Moray Coast Vet Group.

Overeating / Obesity are the most common high risk situations which lead to laminitis. The secret to avoiding laminitis in this situation is not to turn the horse out whilst he is fatter than condition score 3. This means he should not have a fat depot along his crest or at the tail head, around the sheath or udder or over the loins. You should be able to feel his ribs easily by running your hand along his side yet you should not be able to see his ribs.

Limiting the grass intake can be accomplished by using a grazing mask or muzzle or (perhaps more easily) by restricting the area available for grazing.

Treatment

Treatment of laminitis involves the use of anti-inflammatories (non steroidal anti-inflammatories NSAIDs) which also have some pain relieving effect and diet adjustment. NSAIDs such as ‘bute’ are commonly used for around 2 weeks in acute laminitis cases and sometimes indefinitely in chronic laminitis cases. Other Laminitis treatments include:

- Frog supports – to support the sole

- Drugs to improve circulation e.g. ACP the sedative (also reduces stress). Practically most of such drugs have not been shown to help a lot in laminitis treatment.

- Cold therapy. Can help in initial stages of laminitis treatment but the benefits have not been accurately assessed.

- Nerve Blocks to desensitise the feet in laminitis treatment may seem sensible but it may mean that laminitis cases put too much weight on sensitive feet and do more damage.

The horse has a very complex digestive system consisting of the mouth, oesophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine and rectum. The system is designed around the horse grazing for at least 12 hours a day on a diet of grass or similar vegetation.

Horses are unique in the fact that they are unable to vomit due to a muscular valve at the entrance of the stomach preventing food from being regurgitated. In the very rare circumstance when this valve is not functioning properly, food may be regurgitated.

How the horse’s digestive tract works

Colic is a symptom and not a disease; it is indicative that a horse is suffering with pain in its abdominal tract. The behaviour demonstrated by a horse suffering with colic will vary greatly depending on the type and severity of the colic. Colic is an all too common condition and a horse can suffer with colic at anytime; it can affect any horse, of any breed and age. Colic is potentially life threatening and should be treated as an emergency in all instances.

There are a number of types of colic, listed below are the most frequently seen colics in horses:

Impaction

Impaction can occur at various sites within the digestive tract. This type of colic can be caused by indigestible, dry feed such as unsoaked sugar beet pellets that stick together or swell causing a blockage in the digestive tract.

Meconium retention (the first faeces passed by a new born foal) is another cause of impaction colic.

Horses with impaction colic usually experience low grade pain for prolonged periods. This colic can last for several days and is potentially fatal if the horse is not treated promptly.

Spasmodic

Spasmodic colic is the most common type of colic diagnosed in horses. It is often associated with stress and/or excitement. Bouts of short sharp pain caused by spasms of the intestinal walls may be experienced, with loud gut sounds. Recovery may be spontaneous but prompt veterinary attention is still required.

Flatulent

Flatulent colic is also known as tympanic or gas colic. This results from excessive gas accumulation in the large intestine. High pitch gut sounds are commonly associated with this type of colic. Flatulent colic is caused by food materials fermenting in the digestive tract, this is commonly seen in horses which are fed large quantities of fermentable food such as rich spring grass.

Obstructive

There are various types of obstructive colic. Strangulation and mechanical pressure on the gut, are potentially the most serious types of colic. This is different to the blockage caused by a mass of food (impaction) or foreign material such as sand in the intestine. A strangulating obstruction disrupts the blood flow, usually when a piece of the intestine becomes twisted, commonly referred to as a ‘twisted gut’.

Non-strangulating infarction

This usually occurs if a blood vessel becomes blocked, usually affecting an artery that feeds sections of the intestine which then dies. Parasites are a common cause of this type of colic.

Enteritis

Enteritis is inflammation of the small intestine. Diarrhoea or scouring are clinical signs commonly associated with this type of colic.

Symptoms of Colic

The symptoms will depend greatly on the severity and type of the colic; these may include some or all of the following:

- Changes in eating habits, including a loss of appetite

- Continuously getting down to roll and then getting back up again

- Pawing the ground

- Pacing the stable

- Limited or no passage of faeces

- Straining to excrete faeces

- Turning round and looking at their flanks

- Kicking at their abdomen

- Anxious and shivering

- Sweating

- Abnormal temperature, respiratory rate and heart rate

- Excessive urination

All cases of colic must be treated as an emergency and veterinary advice sought immediately when colic is suspected.

Treatment of Colic

Walking a horse with colic to try and prevent it from rolling is traditionally recommended but what is most important is that you ensure that if the horse does go down and roll it can do so safely without getting cast or damaging itself on hard surfaces or projections.

Treatment will vary depending on the type and severity of the colic. The majority of cases can be successfully treated by drugs administered by a veterinary surgeon. Pain relief is often administered to help alleviate the horse’s discomfort. More serious cases such as strangulating colic (twisted gut) that do not respond to medication may be referred for colic surgery. Colic surgery is a complex procedure and may not be an option in every case. Surgery can be expensive and carries a high level of risk for the patient.

Early treatment is essential. Colic surgery can be a complex and lengthy operation with the success rate being less than 100%. It is essential to remember that after-care will be as important as the operation itself, your horse would require extensive after-care for a period of several months, and you could expect him to be off work for a number of months.

Prevention of Colic

Prevention is always better than cure, and following best management practice will help reduce the risk of colic. On occasions however, even with the best intentions, it is impossible to eradicate the risk of colic completely.

Feeding

It is essential that a well balanced diet is tailored to the needs of the individual horse. This should contain plenty of fibre, which is essential for gut mobility. Any changes to the diet should be done gradually; this includes changing feed stuffs, pasture and obtaining forage from a new supplier.

Good quality feed stuffs should always be used. Choosing a cheaper, lower quality feed or forage may compromise the horse’s health and precipitate the onset of colic or respiratory disorders.

Feeds should always be stored in vermin and horse proof containers to prevent any escapee horses gorging themselves on the content of open feed bins.

Some horses choose to eat their bedding materials, some of which are not digestible and can result in impaction colic.

Parasite Control

Every horse owner should have an effective worming programme. Horses need periodic worming to reduce the risk of high parasite burdens which can cause significant damage to the digestive tract including disruption to the blood supply to the intestine, ulcerations and perforations making a horse more susceptible to colic.

Faecal egg counts can be carried out by Moray Coast Vets to determine the worm burden of individual horses which will determine the frequency and type of worming required.

Exercise

Exercise requirements vary but any change in intensity or duration must be gradual. Sudden changes to exercise regimes may result in the onset of colic and other problems. Horses should always be appropriately warmed up and cooled down prior to and after exercise.

Feeding and watering horses in large quantities prior to exercise is not recommended. Similarly, feeding too soon after exercise, before the horse has completely cooled down, also poses the risk of inducing colic.

Water may be offered in small quantities to a horse after exercise but giving very cold water to a hot horse is best avoided.

Once the horse has cooled down normal watering may be resumed.

General Health Care

Horses’ teeth need to be checked regularly, ideally every six months to a year. More attention should be given to young horses whose teeth are growing and constantly changing, and older horses whose teeth may become loose, decayed or have fallen out.

Routine

Horses like routine. Sudden changes to diet, exercise, turnout or owner visiting times may cause stress and induce colic. Good hygiene and daily washing of feed bowls and water containers is vital. Stables should be mucked out daily and fresh bedding added on a regular basis.

Regular checks should be carried out on horses throughout the day and last thing at night to ensure that they are well and have plenty of fresh clean water. If colic symptoms are suspected it is vital to contact your veterinary surgeon immediately and inform them of your concern.

Recognising the symptoms of colic, treating it as an emergency and getting prompt veterinary assistance can potentially save your horse’s life.

For more information see http://www.grasssickness.org.uk

Grass Sickness, a devastating disease first seen in horses in Angus, Scotland around 1907, remains one of the great unsolved mysteries, and consequently one of the most feared by horse owners.

Cases occur in every month of the year but most are seen between April and July with a peak in May. In some years a second, smaller, peak occurs in the autumn or winter. At least in Scotland, the lowest incidence is in August which may be a weather-associated effect (see below).

Predisposing Factors

Grass sickness, as its name suggests, is strongly associated with grazing but there have been a few cases in animals with no access to pasture. In these rare cases, hay has been implicated as the source of the causal agent. Although most cases have been at grass full-time or during the day, the disease can affect horses which have only a few minutes’ access to grass daily. Giving supplementary feeding in the form of concentrates does not have a protective effect, but hay feeding reduced the risk factor in one study.

It is well recognised that certain premises or even fields within single premises are associated with the occurrence of grass sickness cases. Animals which have been on affected premises for less than 2 months are more likely to develop the disease. Commonly, only one animal is affected at a time but ‘outbreaks’ of the disease, with several cases in a period of a few weeks, are not infrequent.

There is no clear association with type of pasture (new ley, permanent pasture, hill grazing, clean or ‘horse-sick’ pasture) but recent evidence suggests that high nitrogen content of soil and soil disturbance may be risk factors. While it was previously thought that grass sickness was more common in pastures with a high clover content, recent studies indicate that it can also occur on pastures with no clover. Thus clover is not the sole cause of the disease, and at worst may be a trigger for a bacterium such as Clostridium botulinum.

Other suggested risk factors include increased numbers of horses on the pasture, mechanical droppings removal and presence of domesticated birds on fields. Stress appears to be a factor in predisposing to the disease and a significant number of animals have a history of recent stress including recent purchase, mixing with strange horses, travelling a long distance, breaking and castration. Animals in good to fat condition also appear to be predisposed.

Many horse owners have firm opinions about the type of weather prevailing when grass sickness cases occur. In a survey of weather conditions in the two weeks preceding multiple-case outbreaks, it was found that cool, dry weather with a temperature between 7 and 11°C was recorded in a statistically significant number of instances. This may partly explain the higher incidence of the disease in the eastern side of Britain where such conditions are more prevalent.

Results of two surveys suggest that the risk of developing grass sickness is slightly higher in horses which are wormed more frequently with certain types of wormers. However, it should be emphasised that the consequences of not worming can be very serious or even fatal and it is not suggested that owners should decrease their use of wormers. There is also no indication that wormers themselves contain the toxin that causes grass sickness.

Causal Agent

The cause of grass sickness is unknown despite almost 100 years of investigation. Many potential causes have been examined over the years including poisonous plants, chemicals, bacteria, viruses, insects and metabolic upsets. A common suggestion by horse owners is that mineral or vitamin deficiencies may be the cause. None have any proven link with the disease, although selenium deficiency, which results in reduced levels of protective antioxidants in the body, may have some role to play. Grass sickness does not appear to be contagious and the type of damage to the nervous system suggests that a toxic substance is likely to be involved. The currently favoured theory under investigation is the possible involvement of Clostridium botulinum, a soil-associated bacterium.

Clinical Signs

Grass sickness occurs in three main forms, acute, subacute and chronic, but there is considerable overlap in the symptoms seen in the three forms. The major symptoms relate to partial or complete paralysis of the digestive tract from the oesophagus (gullet) downwards. In acute grass sickness, the symptoms are severe, appear suddenly and the horse will die or require to be put down within two days of the onset. Severe gut paralysis leads to signs of colic including rolling, pawing at the ground and looking at the flanks, difficulty in swallowing and drooling of saliva.

The stomach may become grossly distended with foul-smelling fluid which may start to pour down the nose. Further down the gut, constipation occurs. If any dung is passed, the pellets are small, hard and may show a ‘cheesy’ coating of mucus. Fine muscle tremors and patchy sweating may occur. In this form, the disease is fatal and the horse should be put down once the diagnosis is made. In subacute grass sickness, the symptoms are similar to those of the acute disease but are less severe. Accumulation of fluid in the stomach may not occur but the horse is likely to show difficulty swallowing, mild to moderate colic, sweating, muscle tremors and rapid weight loss. Small amounts of food may still be consumed. Such cases may die or require to be put down within a week.

In chronic grass sickness, the symptoms come on more slowly and only some cases show mild, intermittent colic. The appetite is likely to be reduced and there will be varying degrees of difficulty in swallowing but salivation, accumulation of fluid in the stomach and severe constipation are not a feature. One of the major symptoms is rapid and severe weight loss which may lead to emaciation. Previously, it was thought that nearly all such cases died and that the few which survived made only a partial recovery and were subsequently useless for work. This is now known to be incorrect (see section on treatment).

Diagnosis

The symptoms described above may seem quite clear-cut but unfortunately not all affected animals show all these signs and it can sometimes be very difficult for the veterinary surgeon to distinguish grass sickness from other causes of colic, difficulty in swallowing and weight loss. This is compounded by the fact that there is no non-invasive test for diagnosing the disease in the live animal.

A definite diagnosis can be made only by microscopic examination of nerve ganglia after death or by surgical removal of a piece of small intestine by opening the abdomen. Characteristic degenerative changes in the nerve cells can then be demonstrated in the tissues. A test involving application of 0.5% phenylephrine eye drops, which reverses the drooping eyelids seen in grass sickness, has shown potential as a test for use in the live horse.

Treatment/Management

As previously stated, treatment should not be considered in acute and subacute cases. However, in chronic cases, if the animals are not in much pain, can still eat at least a small amount and are still interested in life, treatment can be attempted. The correct selection of potentially treatable cases using these criteria requires experience and is essential. Not all chronic cases are treatable. The management of selected cases has been the subject of study by the Grass Sickness Research Team at Edinburgh University Vet School since 1989 and the results have challenged the view that chronic cases either die or at best only partly recover.

Management of chronic cases involves provision of palatable, easily swallowed food e.g. chopped vegetables, grass and high energy concentrates soaked in molasses. It is essential that high energy foods are consumed as chronic cases fed roughages and succulents alone will invariably die. Nursing is also vital and provides the mainstay of management. The patients require constant stimulation by human contact, frequent grooming to prevent them becoming scurfy and sticky with sweat and, in some cases, rugging which has been found to reduce sweating and prevent hypothermia.

By careful attention to the management regime the recent recovery rate for carefully selected cases in the Easter Bush Veterinary Centre Equine Hospital is now approximately 70% and veterinary practitioners in the field report success when following the same regime. Contrary to commonly held views, a follow-up study has shown that 41% of these recovered cases were back to work including hunting, racing, eventing, 33% were being hacked, preparing for competitive work or being used for breeding and the other 26% (the more recent cases) were still gaining weight and recovering at the time of the survey. None of the survivors were described as being of no use. This represents a major improvement in the prognosis for such cases compared with the situation before the late 1980s.

Causes

Until the cause is known, it is difficult to give sound advice regarding prevention. In areas where the disease is prevalent, stabling the animals during the spring and early summer will reduce the likelihood of disease. Following the discovery of an association with weather, some owners living in affected areas now stable their horses when dry weather with a temperature of 7-11°C has persisted for 10 consecutive days.

Stabling is particularly advisable for a new horse that has been moved onto premises where the disease is known to occur. If certain fields are ‘bad’ for the disease, they can be grazed by other stock, especially in spring and summer. If a case occurs amongst a group of horses, it is probably best to move the others out of that field provided this does not involve too much stress associated with transportation or mixing with strange horses.

For more information, see http://www.sweetitch.co.uk

The Symptoms of Sweet Itch

Sweet Itch, or Summer Seasonal Recurrent Dermatitis (SSRD), is a problem that affects thousands of horses, ponies and donkeys in many countries of the world to a greater or lesser degree. Virtually all breeds and types of ponies and breeds can be affected, from tiny Shetland ponies to heavyweight draught horses, although the condition is rare in Thoroughbreds. About 5% of the UK horse population are thought to suffer.

Symptoms include severe pruritus [itching], hair loss, skin thickening and flaky dandruff. Exudative dermatitis [weeping sores, sometimes with a yellow crust of dried serum] may occur. Without attention sores can suffer secondary infection.

The top of the tail and the mane are most commonly affected. The neck, withers, hips, ears and forehead, and in more severe cases, the mid-line of the belly, the saddle area, the sides of the head, the sheath or udder and the legs may also suffer.

The animal may swish its tail vigorously, roll frequently and attempt to scratch on anything within reach. It may pace endlessly and seek excessive mutual grooming from field companions. When kept behind electric fencing with nothing on which to rub, sufferers may scratch out their mane with their hind feet and bite vigorously at their own tail, flanks and heels. They may drag themselves along the ground to scratch their belly or sit like a dog and propel themselves round to scratch the top of their tail on the ground.

There can be a marked change in temperament – lethargy with frequent yawning and general lack of ‘sparkle’ may occur, or the horse may become agitated, impatient and, when ridden, lack concentration. When flying insects are around he may become agitated, with repeated head shaking.

Diagnosis is not usually difficult – the symptoms and its seasonal nature (spring, summer and autumn) are strong indicators. However symptoms can persist well into the winter months, with severely affected cases barely having cleared up before the onslaught starts again the following spring.

Horses that go on to develop Sweet Itch usually show signs of the disease between the ages of one and five and it is common for the symptoms to appear first in the autumn.

There is anecdotal evidence that stress (e.g. moving to a new home, sickness, or severe injury) can be a factor when mature animals develop Sweet Itch.

Hereditary predisposition may be a factor in Sweet Itch and work to identify the gene(s) responsible is at an early stage. However environmental factors play a major part – where the horse is born and where it lives as an adult are at least as significant as the bloodlines of its sire and dam.

Sweet Itch is not contagious, although if conditions are particularly favourable to a high Culicoides midge population, more than one horse in the field may show symptoms.

In the UK Sweet Itch is classified as an unsoundness and, as such, should be declared when a horse is sold.

Cause and Culprits

Sweet Itch is an allergic reaction and therefore an immune system problem. Unfortunately these are notoriously complicated and difficult to deal with.

The disease is a delayed hypersensitivity to insect bites and results from an over-vigorous response by the animal’s immune system. In the process of repelling invading insect saliva (which actually contains harmless protein) the horse attacks some of its own skin cells ‘by mistake’ and the resulting cell damage causes the symptoms described as Sweet Itch.

In the UK several species (of the 1,000 or so that exist) of the Culicoides midge are responsible. Culicoides adults mainly rest among herbage and are most active in twilight, calm conditions. Breeding sites are commonly in wet soil or moist, decaying vegetation. They are tiny, with a wing length less than 2 mm and able to fly only a short distance (100 metres or so).

Male Culicoides are nectar feeders, but soon after hatching the females mate and require a blood meal to mature their eggs. They do not fly in strong wind, heavy rain or bright, clear sunshine. They dislike hot, dry conditions. The grey light at dusk and dawn suits them well, and they are at their most active at these times. However, as they are poor fliers, if there is too strong a wind, or rain during early morning, they will simply wait until later to feed. Likewise they may feed at any time during humid days with cloud cover.

Culicoides are on the wing and breeding from as early as late March until the end of October, depending on geographical location. There is only a short breeding season each year in the north of Scotland, while in the south of England larvae will hatch throughout the spring, summer and autumn, depending on weather conditions. Seasonal variations in the weather can have an impact – recent winters have been milder and damper allowing breeding to start earlier. Summers that are alternately sunny and rainy cause an increase in midge breeding habitats and therefore an increase in the numbers of midges that are around to bite. Under these conditions most horses will show symptoms of Sweet Itch to some degree. Culicoides numbers are the critical factor.

Culicoides larvae are able to survive severe frosts but they do not survive prolonged drought conditions.

Management

At present there is no cure for Sweet Itch. Once an animal develops the allergy it generally faces a ‘life-sentence’ and every spring, summer and autumn are a distressing period for horse and owner alike. The animal’s comfort and well being are down to its owner’s management.

There are two basic approaches:

1. Minimise midge attack

- Avoid marshy, boggy fields. If possible move the horse to a more exposed, windy site, e.g. a bare hillside or a coastal site with strong onshore breezes. Chalk-based grassland will have fewer midges than heavy clay pasture.

- Ensure pasture is well drained and away from rotting vegetation (e.g. muck heaps, old hay-feeding areas, rotting leaves).

- Stable at dusk and dawn, when midge feeding is at its peak, and close stable doors and windows (midges can enter stables). The installation of a large ceiling-mounted fan can help to create less favourable conditions for the midge.

For slight to moderate cases of Sweet Itch this can help. However a seriously itchy, stabled horse has hours of boredom during which to think up new ways of relieving his itch – manes and tails can be demolished in a few hours of scratching against a stable wall. If stabling can be avoided it is best to do so.

Use an insect repellent.

Some are effective against flies but their effectiveness against Culicoides is unproven. DEET (the acronym for N,N-Diethyl-m-toluamide), has a track record stretching back over 40 years and has proven to be highly effective. It is the active ingredient in many midge and mosquito repellents for use by people. Research has shown that the higher the concentration of DEET in a repellent the more effective and long-lasting it is likely to be.

Use an insecticide.

Some owners achieve good results with insecticides whilst others find they have shown little benefit in controlling Sweet Itch.

Benzyl benzoate was originally used to treat itch-mites (scabies) in humans and has been used for many years to combat Sweet Itch. In its neat form it is a transparent liquid with an aromatic smell, but it is more commonly obtained from Vets or pharmacies as a diluted milky-white suspension. It is listed as an ingredient in several proprietary formulations, including Carr, Day & Martins’ ‘Kill Itch’ and Pettifer’s ‘Sweet Itch Plus’.

Benzyl benzoate should be thoroughly worked into the skin in the susceptible areas every day. However it is a skin irritant and should not be used on the horse if hair loss and broken skin have occurred – application should therefore start before symptoms develop in the spring. If used later its irritant properties can cause areas of skin to slough-off, in the form of large flakes of dandruff.

Other insecticides, including permethrin and related compounds, tend to be longer lasting but should also be used with care. Permethrin is available by veterinary prescription (e.g. Day, Son & Hewitt ‘Switch’ pour-on liquid). Application instructions should be followed.

Note: Gloves should be worn when applying insecticides, including benzyl benzoate. Particular care should be taken if they are used on ponies handled by children – they can cause eye irritation, for example if fingers transfer the chemical from the pony’s mane to the eyes.

Coat the susceptible areas of the horse with an oil . Midges dislike contact with a film of oil and they will tend to avoid it. Commonly used preparations include Medicinal Liquid Paraffin, and ‘Avon Skin-so-Soft’ bath oil (diluted with water). There are several oil-based proprietary formulations, for example Day Son & Hewitt’s ‘Sweet Itch Lotion’.

Oils and other repellents that are effective usually work for a limited time: In summer a horse’s short coat-hair does not retain the active ingredient for long and it can be easily lost through sweating or rain. Re-application two or three times every day may be necessary.

Greases (usually based on mineral oils) stay on the coat longer, but they are messy and therefore not ideal if the horse is to be ridden. They can be effective if only a small area of the horse is to be covered. However it is impractical and often expensive to cover larger areas.

Some preparations contain substances (e.g. eucalyptus oil, citronella oil, tea tree oil, mineral oil or chemical repellents) that can cause an allergic skin reaction. Always patch test first on the neck or flank of the horse – apply to an area about 3 cm across and look for any sign of swelling or heat over a 24 hour period before using more extensively.

Use a Boett® veterinary blanket. This is by far the most effective Sweet Itch protection to date and avoids the need need to use insecticides, oils or greases.

The Boett (pronounced Bo-ett, as in Go-get!) Blanket was invented in Sweden 16 years ago to offer protection to horses and ponies suffering from insect-bite allergy. It has been continually developed since then and is now used around the World as the best way to manage Sweet Itch, whilst avoiding undesirable side effects.

The blanket is made from a purpose-designed fabric, (not a mesh) which midges cannot bite through. It offers COMPLETE protection to all parts of the horse that it covers and the soft fabric does not damage the hair. The fabric is light but strong, so the horse can wear the blanket 24 hours a day, month after month, in total comfort.

Ideally the horse should start wearing the blanket before symptoms appear, but even later in the season, once the blanket is fitted, sores will quickly heal and mane and tail growth restart. Typically it will take from one to three weeks after the blanket is fitted for damaged skin cells to recover and itchiness to decline. Horses wearing the blanket all summer keep their full manes and tails and have glossy, clean coats and those susceptible to sun sensitivity and contact nettle rash are also helped.

2. Allow midge attack, but try to minimise the resultant allergic reaction by:

- Depressing the immune system with corticosteroids (e.g. by injection of ‘Depo-Medrone’ or ‘Kenalog’, or in tablet form as ‘Prednisolone’) may bring temporary relief but there can be side effects, including laminitis, in some animals. With time, corticosteroids may become less effective, requiring ever larger and more frequent doses.

- The use of anti-histamines may bring some relief but high dose rates are required and they can make the horse drowsy.

- Applying soothing lotions to the irritated areas. Soothing creams such as Calamine Cream or ‘Sudocrem’ can bring relief and reduce inflammation, but they will not deter further midge attack. Steroid creams can reduce inflammation.

It is often difficult to assess the effectiveness of a particular treatment. The incidence and severity of Sweet Itch is so highly dependent on midge numbers, apparent success may simply reflect a temporary fall in numbers due to a change in the weather, for symptoms only to return again later when weather conditions are more midge-favourable.

We have a state of the art therapeutic laser unit, which can be used as a treatment for a range of inflammatory conditions, primarily for dogs and cats, but also for horses. Therapeutic laser can be used as a treatment for pain and inflammation, in joints and soft tissue. Its main use is for treatment of chronic conditions such as osteoarthritis, but it can also be used to aid healing of skin wounds.

In cases of arthritis, the laser can be used in conjunction with traditional anti-inflammatory medications, or in some cases, may be sufficient on its own.

Following surgical procedures, a short application of laser can reduce swelling and speed up recovery.

Laser is a quick and painless procedure. It can be performed on an outpatient basis without sedation, and usually takes about 20 minutes.

It can be done at the Forres surgery or at a visit.

Please ask at reception if you require more details.

Copyright 2018 Moray Coast Vets Group | Design by Cuan